ebola virus prevention and treatment

Prevention and control

Good outbreak control relies on applying a package of

interventions, namely case management, surveillance and contact tracing,

a good laboratory service, safe burials and social mobilisation.

Community engagement is key to successfully controlling outbreaks.

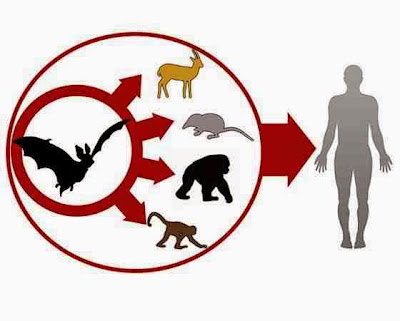

Raising awareness of risk factors for Ebola infection and protective

measures that individuals can take is an effective...